Blog

The HE Debate: Where next for...internationalisation?

20 Jan 2015

Professor Robin Middlehurst, Professor of Higher Education, Kingston University

Professor Robin Middlehurst, Professor of Higher Education, Kingston University

“Universities and higher education fuel growth in far more ways than we realise. And long-term, stable economic growth is how we secure a truly great future for this remarkable country.” Rt Hon David Willetts MP, former Universities and Science Minister to Universities UK Conference, 03.04.14

For many commentators inside and outside the higher education sector, the ‘internationalisation’ aspirations of higher education institutions are understood narrowly in terms of recruiting international students to the UK.

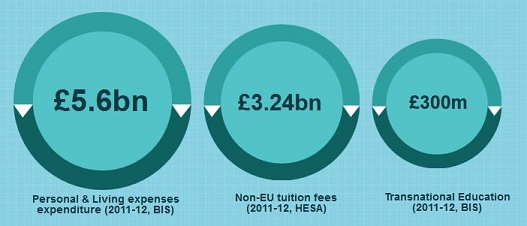

Such recruitment is certainly important in economic terms: HESA data report that the total of non-EU students’ tuition fees to UK universities was £3.24bn in 2011-12. The Department for Business Innovation and Skills (BIS) calculations for the same period estimated that expenditure on personal and living expenses by international students (EU and non-EU) amounted to a further £5.6bn of export earnings, while UUK’s recent modelling suggests that an estimated £4.9bn of this sum is spent off-campus (UUK, 2014).

Recruiting international students overseas in various forms of transnational education (TNE) is also economically significant, the BIS estimate for 2011-12 was £300m (BIS, 2013a) while a forthcoming BIS report on the value of TNE to institutions and the UK shows considerable growth in volume and value of TNE since these estimates were made.

Beyond international student recruitment, UUK also calculated the economic value of international visitors brought to the UK through universities’ educational activities (excluding the friends and families of international students). Universities host a wide range of international visitors including attendees at learned societies’ academic and professional conferences, those leisurely visiting the UK, participants on group tours and summer schools as well as a range of visiting international scholars and researchers. The value of personal off-campus expenditure for these international business visitors in 2011-12 was estimated, conservatively, at £136m in UK export earnings (UUK, 2014).

Developing research internationally

Universities’ research income from international sources is growing. In a ten year period from 2001-2011, the total amount of research grants and contracts from non-EU sources grew from approximately £0.1bn-£0.2bn while those from EU sources grew still more from approximately £0.2bn-£0.5bn (UUK, 2013).

Universities create economic, social and intellectual value from their research outputs, including scholarly publications. The Publishers’ Association estimated that 80-90% of learned journal turnover arises from exports, with total turnover (domestic and export) in 2011 approximating £1bn- £1.5bn. Exports contributed at least £507m (BIS, 2013). In terms of research citations, the UK accounts for 11.6% of global citations and 15.9% of the most highly cited articles. Amongst its comparator countries, the UK has overtaken the US to rank 1st in field-weighted citation impact (a measure of research quality) (BIS, 2013). The UK ranks second against its comparator countries in the international mobility of its researchers; 71.6% of active researchers were internationally mobile in the period 1996-2012 (BIS, 2013).

International collaboration is often linked to such mobility. In 2012, 47.6% of all UK articles resulted from international collaboration. Co-authorship is typically associated with high field-weighted citation impact, for both partners (BIS, 2013). The authors of the BIS report comment that the UK occupies a central position in the global collaboration network, with Western European partners being of high importance. International collaborations, both disciplinary and multi-disciplinary, are seen by scientists and other stakeholders as essential to tackling a number of global challenges such as climate change, poverty, energy, security and the spread of infectious diseases. Research collaborations are extending beyond other universities to include industry, third sector bodies, charitable trusts and arts’ organisations.

The wider benefits of internationalisation

Metrics on the social and public value of higher education are less well-advanced and embedded in the UK than economic measures (Kelly & McNicholl, 2011). A recent study on the wider benefits of internationalisation from the perspective of non-EU international alumni who had studied in the UK is therefore welcome (BIS, 2013). Students were overwhelmingly positive and reported benefits on several dimensions. Wider ‘influence’ benefits to the UK included being informal ambassadors, promoting trust in the UK as a nation, society, its enterprises and individuals, and bringing UK values into capacity-building in home countries. The graduates reported individual gains in terms of career development, English language proficiency, personal growth and wider experiences (such as part-time work and volunteering), social benefits and networks, increased cosmopolitanism and inter-cultural awareness. Benefits to home countries were also highlighted including acquisition of new skills and development of new careers, as well as broader societal and political impact.

The British Council in partnership with the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) has recently reported on the impact of transnational education (TNE) (i.e. programme and provider mobility) on host countries (BC & DAAD, 2014). The UK leads in TNE and the findings suggest it is having positive benefits in reaching relatively mature students, perhaps encouraged by flexible delivery combined with opportunities to enhance professional skills and career development. TNE involving work placements and internships was particularly valuable as gaining an international outlook with greater intercultural awareness and competence was highly ranked by students. TNE stakeholders beyond students reported on the value of TNE in providing increased access to higher education for local students and improving the overall quality of provision. It was also more affordable than studying overseas (although more expensive than local provision). On the other hand, the British Council argues that more could be done to plug skills’ gaps in local labour markets and in providing niche programmes unavailable locally.

Collaboration and partnership

While competition between institutions and countries is emphasised in studies of internationalisation, collaboration is of fundamental importance and partnerships of all kinds have been growing. Such partnerships can make a significant contribution to the UK’s reputation for innovation as well as sustainability of international links and relationships (million+, 2009). The conclusions from a study of 28 universities across the UK demonstrate that institutions participate in inter- and multi-national research projects with highly-regarded education and business-sector organisations, often in applied fields that directly address global issues and problems. They have significant numbers of well-established and mutually-beneficial teaching partnerships involving professional and technical disciplines, enrolling large numbers of students. Institutions engage in entrepreneurial and knowledge-transfer activities in areas such as CPD, support for business and the development of science parks overseas and they partner with institutions in developing countries for capacity-building in research, CPD and development. They also have worldwide partnerships that facilitate student and staff mobility and exchange to and from the UK.

Deepening cultural understanding

Both institutions and countries are becoming more sophisticated in approaches to internationalisation as the development of academic and educational cities in the Middle East, and knowledge and educational hubs in the Far East, testify. Developing nations are inviting overseas’ institutions to contribute to capacity-building, quality improvement and innovation, while developed nations including the UK are hosting overseas’ institutions from a variety of countries. Governments are making links across science, innovation, education and training policies and universities are responding as active partners in ‘triple helix’ alliances between academia, industry and government. Institutions’ international strategies are aiming to combine and leverage opportunities for research, teaching and knowledge transfer. Collaborations that may begin with individual scholarly relationships are extending to deeper strategic institutional partnerships across countries. Institutions are also seeking to extend and develop their alumni relationships and networks to benefit new graduates and businesses as well as to bring political, social, cultural and economic capital to the UK. Universities are thinking strategically about the economic and social collaborative potential of their cities and regions. They are partnering with businesses locally to access international opportunities that bring business and educational value simultaneously, collaborating with arts and cultural organisations to develop new research and educational opportunities overseas, and are identifying the potential for cultural exchange between local diaspora and their home communities.

Maximising the impact of internationalisation

Sophistication in internationalisation also extends to seeking new ways to gather data and measure the impacts of internationalisation for a variety of stakeholders, paying attention to positive and mutually beneficial impacts as well as cost-benefit analyses of financial and reputational risk, the potential for brain-drain and negative environmental impact. Universities and colleges are also addressing internationalisation agendas ‘at home’ for those who cannot travel overseas for study, work or volunteering opportunities as students, recognising that language skills and the capacity for intercultural dialogue is becoming a key skill for graduates as well as for businesses and communities across the UK. The European Commission’s communication on “Europe in the World” (EC, 2013) points in the same direction, promising more funding and support for internationalisation and arguing for the reduction of barriers to internationalisation such as immigration policy and portability of qualifications. The Commission outlines three key priority categories for countries and institutions in developing ‘comprehensive internationalisation’: international staff and student mobility; internationalisation of curricula and digital learning; and strategic co-operation, partnerships and capacity-building. UK institutions are at various stages of development towards ‘comprehensive internationalisation’ and need to remain ahead as others raise their game.

In the next Parliament, investment in comprehensive internationalisation should be a priority for all countries of the UK since there is already clear evidence that such investment yields substantial dividends.