Blog

CEO Blog: The postgraduate problem: does the treasury have a solution?

01 Dec 2014

If the political gossip mill and Treasury briefings are to be believed, ‘solving’ the postgraduate problem is likely to feature in George Osborne’s 3rd of December Autumn Statement. The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) has been on the postgraduate plot for a couple of years. Not to be outdone the Scottish Government recently announced a review with the aim of improving postgraduate participation. As the main Opposition Party, Labour has also said that access to postgraduate study needs to be addressed as part of any new funding settlement. In fact there have been a slew of reports going back a number of years, including one published by million+1, which have called on governments to adopt pro-active strategies to promote postgraduate study. Subject to the engine room detail (which will be key), any proposal from the Chancellor of the Exchequer to support postgraduate participation will therefore be a victory of sorts.

If the political gossip mill and Treasury briefings are to be believed, ‘solving’ the postgraduate problem is likely to feature in George Osborne’s 3rd of December Autumn Statement. The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) has been on the postgraduate plot for a couple of years. Not to be outdone the Scottish Government recently announced a review with the aim of improving postgraduate participation. As the main Opposition Party, Labour has also said that access to postgraduate study needs to be addressed as part of any new funding settlement. In fact there have been a slew of reports going back a number of years, including one published by million+1, which have called on governments to adopt pro-active strategies to promote postgraduate study. Subject to the engine room detail (which will be key), any proposal from the Chancellor of the Exchequer to support postgraduate participation will therefore be a victory of sorts.

million+ has long predicted that the 2012 HE reforms in England were likely to prove to be a major disincentive to postgraduate participation, adding to an already parlous state where postgraduate funding received little (if any) funding support. The high sticker price for undergraduate fees in England will create a larger debt burden for new graduates (and whatever people say, graduates will view it as a debt to be paid rather than a tax on higher earnings). However, the lifting of the undergraduate fee cap in England was also accompanied by the withdrawal of HEFCE direct grant for some postgraduate teaching (funding which had already been reduced prior to the 2012 reforms).

This double whammy for postgraduate education becomes a triple whammy once the impact of the recession and slow economic growth on household incomes are factored in. Politicians may finally have caught up with the plot: postgraduate study is increasingly the preserve of those with financial means and risks becoming a further and fundamental barrier to social mobility.

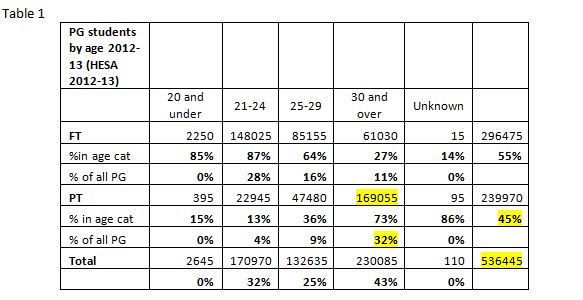

Any move to introduce loans for postgraduate taught master’s degrees is likely to be welcomed at least in principle. However, it will be disappointing if the Chancellor’s solutions focus primarily on the issues faced by those on ‘traditional’ HE journeys – essentially younger full time undergraduates who enter university with A-levels and who want to move directly on to full time postgraduate study. These students are, of course, an important constituency, but as Table 1 illustrates, the postgraduate story is far more complex. According to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency, in 2012-13 there were 536,445 postgraduate students (in an overall student population of 2.3 million). Of those postgraduate students 45% were studying on a part-time basis. What’s more, nearly one-third – almost 170,000 students - were over the age of 30 years old.

These statistics cast a sharp light on the debate around higher education and social mobility. Too often this has perpetuated the myth that the postgraduate problem will be solved by providing more support for younger full-time students who have just completed their first degree. As has been demonstrated all too well following the hike in undergraduate fees in England in 2012, the failure to anticipate the impact of changing funding regimes on mature and part-time students can have disastrous consequences on participation.

Any postgraduate ‘solution’ focused on one small part of the postgraduate population i.e. those who study full-time immediately after completing their first degree, will be of limited value. It would also be unhelpful to concentrate on the issue of accessing the professions at the expense of addressing other challenges.

Any postgraduate loan scheme must therefore be accessible and geared to part time and returning students and its success evaluated in terms of outcomes for older students, those who have already had experience of the workplace and who want to specialise further or change career.

It would also be tempting for the Treasury to insist that access to any postgraduate fee loan scheme should be means-tested and linked to household earnings. This would be complex and cumbersome to administer and mean that different parameters would be applied to a postgraduate and the undergraduate support scheme currently in place since it is only maintenance loans and grants under the latter that are means-tested. More to the point, access to a postgraduate fee loan scheme linked with an earnings threshold would be more likely to leave older students with higher incomes but with caring and other responsibilities, out in the cold.

Those who advocate that scholarship systems provide the answer are also barking up the wrong tree. Students would be faced with a postcode lottery based on the wealth or otherwise of their university rather than the quality and relevance of the course and the qualification for which they wished to study.

There are, however, important questions about how and when the repayment of postgraduate fee loans should be triggered. Repayment should clearly not be triggered during the course but repayment conditions are likely to be a major factor in the success or otherwise of a loan scheme. A recent IPPR and London Economics report2 calculated that, once postgraduate students have graduated, repayment could be triggered at a lower salary threshold than for undergraduate loans. In principle, these proposals seem to work.

However, a postgraduate loan scheme will have to be funded and will require investment upfront. Universities and students are likely to consider that funding a postgraduate loan scheme by removing or diverting funding from undergraduate study or raiding yet again the Student Opportunity Allocation which supports undergraduate students would be a pretty rum deal. The Chancellor will therefore have to demonstrate beyond any shadow of doubt that any scheme to support postgraduate students is based on new investment.

The Treasury may also be tempted to limit numbers and restrict the courses to which such a loan scheme might apply. The consequences of such constraints need careful consideration. It would be a mistake, for example, for the government to revert to type and favour STEM subjects at the expense of others. Such an approach would cut out whole sectors of the creative and other industries, disadvantage some businesses and curtail the potential for collaborations linked to postgraduate study between universities and many small and medium sized enterprises.

Nor should student numbers at postgraduate level be limited if a loan scheme is introduced and institutions must be free to set fee levels. However, a contribution to postgraduate fees provided via a loan scheme and additional direct investment in postgraduate teaching may breathe some life back into the postgraduate market.

The government should also consider the merits of using any new initiative to stimulate regional economic growth. This is not the same as devolving science investment to city-regions as recently mentioned by George Osborne in Manchester which would be an extremely bad idea. However, as outlined in the million+ report Smarter Regions Smarter Britain there would be great merit in the government investing in 50,000 additional postgraduate places linked with professional, industry and public-service based programmes.

Universities are constantly being told by politicians that they are vital to growth and to increasing social mobility. The right kind of investment by government in postgraduate provision – a neglected space for such a long period of time – would help to achieve both of these goals.

1million+ A postgraduate strategy for Britain, March 2010

2 IPPR Reaching higher: Reforming student loans to broaden access to postgraduate study Oct 2014

Twitter: @millionplusCEO